In terms of FAQs related to club finance, the volume of inquiries we get about debt is second only to questions about food & beverage profitability. The most common question on debt is “how much debt is appropriate?” Discerning the answer to that question begins by understanding how debt fits into the capital mix in a private club.

Research with hundreds of clubs over the last 12 years crystallized the concept: Debt is a supplement to member’s equity, not a substitute for member’s equity. Unfortunately, too many clubs treat it as a substitute. The cultures of many clubs have fermented to a situation where it is easier to ask a bank for money to invest than it is to ask the members for that money. Of course, the obvious conundrum in that scenario is that the only way to pay off debt is through an infusion of equity from the members.

The existence of a culture spectrum within clubs is another concept that has been revealed through our research over the years. On one end of the spectrum are members who think like customers. That mindset is to get as much as possible but pay as little as possible. On the other end of the spectrum are members who think like owners and stewards. Their main desire is to do the right thing and pass the club they love on to the next generation in better shape than it was in when they joined. If every club board provided leadership to the membership by embracing the concept that members are owner and stewards, the entire industry would be healthier for it. Unfortunately, misconceptions get in the way, but that is a topic for another issue of Club Business.

The appropriate use of debt in the capital mix strikes to the heart of the customer-versus-owner mentality. Every club has a mix of members; some think completely as owners and others think completely as customers. In any given club, a majority of members congeal into one camp or the other over time. Clubs in which the members congeal around a customer mentality (“don’t ask me for more money”) are the clubs in which debt becomes a substitute for member’s equity. In clubs with a culture of ownership/stewardship, members understand their obligation to contribute the necessary capital, which manifests financially as member’s equity, to improve the club. In essence, they have pride of ownership and it shows.

In the context of this analysis, the term “debt” refers to third-party debt: mortgage debt, lines of credit and lease debt. It is one of three main tiers of liabilities along with short-term liabilities (accounts payable, accrued payroll, etc.) and member bonds. Short-term liabilities are really anchored to the operating ledger and the operations of the club, which puts them outside the scope of this analysis. The bond issue is left to future analysis because bonds are a hybrid of equity and debt and a topic worthy of its own white paper. This analysis will focus specifically on third-party debt. On a side note, the Club Benchmarking balance sheet data presented in this analysis does consider overall liabilities to equity simply by capturing the Liabilities-to-Assets ratio as well as the Equity-to-Assets ratio.

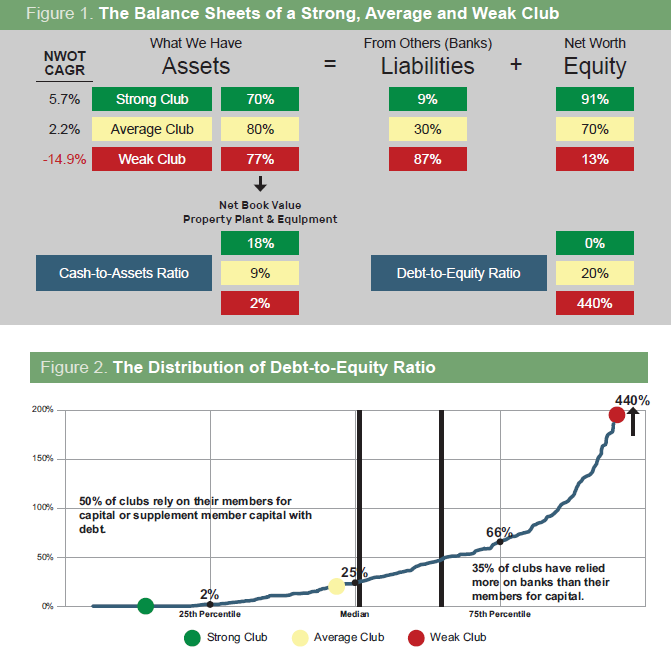

Figure 1 presents the balance sheets of three clubs: a strong club, the average club and a weak club. For the record, the strong and weak clubs in this example are real clubs, which is how we know that the strong club has an owner/steward culture that was born in the mid 1950s when the members began funding depreciation through recurring capital dues, which is of course, members infusing equity. Thus, the club’s obligatory capital needs (the capital necessary to maintain and replace the assets the club owns) have been met on a “pay as you go basis,” freeing initiation fee income since that time for aspirational capital investment, which is growth capital to add to and expand the asset base over time.

The strong club shown in green is exceptionally healthy as evidenced by the balance sheet. Anecdotally, we know this club offers a compelling member experience through an amazing array of services and amenities delivered to members on a campus where the physical assets are always fresh and up to date. The members, in their role as owners, have consistently contributed the capital necessary to maintain the asset base. Since 2006, the club’s net worth (member’s equity) has increased at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.7%. This club does not need debt as a supplement to equity because the members have consistently provided the capital necessary for investment through a combination of recurring capital dues and initiation fees—the ideal combination.

On the other side of the coin is the weak club. Over time, that club, through decisions in the boardroom has fostered, and members have migrated to, a customer mentality. The members are loath to infuse capital. The club attempts to compete on price rather than member experience and value with a nearly nonexistent initiation fee (any deal will do) that allows members to come and go readily due to lack of “skin in the game.” They do not see themselves as stewards or owners and they are not concerned about the club’s future. Since 2006, the club’s Net Worth has fallen dramatically, declining at a CAGR of -15%. The last big “capital raise” was funded by a bank with debt resulting in the lopsided 440% debt-to-equity ratio you see in the chart. This club, literally, found it easier to ask a bank for money than their transitory members, using debt as a substitute for member’s equity. It is a worrisome scenario that is not likely to end well unless the club educates its members about their role as stewards and the fact that ultimately, if the club is to survive, they must begin to contribute equity.

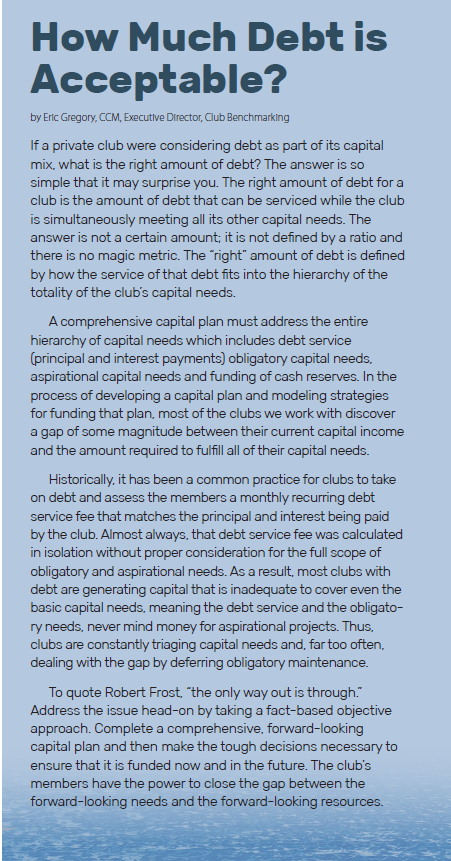

The average club, shown in yellow in Figure 1, more closely resembles the strong club than the weak club. The average club is using debt as a supplement to member equity. Figure 2 presents the distribution of the debt-to-equity ratio for more than 800 clubs. As shown on the chart, 35% of clubs are leaning more on banks to finance capital investment than on their members. They are choosing to use debt as a substitute for member’s equity with the resulting debt-to-equity ratio being greater than 50%. Half of clubs are essentially using debt as a supplement to member’s equity.

In Table 1 below, you see certain key performance indicators (KPI) for the group of clubs with a debt-to-equity ratio below 25% compared to the group of clubs with a debt-to-equity ratio higher than 50%. The data presented is the median for each of those groups.

The most telling KPI is the net worth (aka member’s equity and, for clarity, in a 501(c)(7) member-owned club it is referred to as unrestricted net assets). In the under-25% group, the median equity is $15.2 million, which is nearly three times larger than the clubs with a debt-to-equity ratio above 50%. We conclude that these cultural mindsets form over long periods of time. Clubs that lean on debt have done so over time. These clubs have effectively trained their members to think like customers and they tend to compete on the price they charge, as opposed to the value they offer. The data in Table 1 provides ample support for that conclusion. The initiation fee for those clubs is nearly three times lower, the operating dues for a full member are nearly 20% lower and the dues-to-revenue ratio is 10% lower. Those KPIs paint a picture of the member mindset at that club. On the margin, those clubs have been expecting less of their members for a long time. They use debt as a substitute for member’s equity and they have conditioned their members to embrace that mindset.

Net available capital (effectively earnings before depreciation) is the amount of money a club has at the end of a year to meet the hierarchy of capital priorities; debt service, obligatory capital investment, aspirational capital investment, and increasing cash reserves. The net available capital ratio is net available capital divided by the operating revenue, which normalizes the metric for club size. Club Benchmarking recommends clubs should target a net available capital ratio of more than 18% year-in and year-out.

As the table shows, the group of clubs with a debt-to-equity ratio above 50% has a net-available-capital ratio of 12% at the median, which is 20% lower than the 15% ratio for the group with debt-to-equity less than 25%. Compounding the reality of having less capital available is the fact that the significantly higher debt must be serviced. The principal and interest payments for the debt comes out of net available capital, meaning the clubs with debt-to-equity above 50% will have much less free cash available after covering debt service to penetrate the remaining capital priorities: obligatory capital investment, aspirational capital investment and increasing cash reserves.

Table 1 – Certain Key Performance Indicators Based on Debt-to-Equity Ratios

| Debt-to-Equity Ratio | 0-25% | >50% |

| Initiation Fee | $45,000 | $17,000 |

| Full Member Operating Dues | $9,100 | $7,700 |

| Operating Dues to Operating Revenue Ratio | 53% | 48% |

| Net Available Capital Ratio | 15% | 12% |

| Net Worth (aka Member’s Equity) | $15,200,000 | $5,500,000 |

| Net Book Value of Property, Plant & Equipment | $12,400,000 | $8,800,000 |

| Debt | $400,000 | $5,300,000 |

Having done a deep dive analysis of the use of debt across the industry, let’s review the insight to discuss when and how debt is appropriate in the capital mix.

In terms of the two categories of capital investment, obligatory and aspirational, it is appropriate to use debt for aspirational investment but much less appropriate, even inappropriate, to use debt to cover obligatory investment. Circling back to the strong club’s approach as the best practice model, members are covering obligatory capital through recurring capital dues in a pay-as-you-go manner. That approach assures every member pays their fair share of the capital they consume during their tenure as a member. Thus, they will not leave their obligation behind for another member when they leave the club. When a club uses debt to make obligatory investment, a choice has been made (typically an unconscious choice) to shift the burden for the consumption of those assets (depreciation) from the past or more tenured members who consumed those assets to the future members who will be responsible for paying the debt back through their contribution of capital. Although it happens often, using debt to cover obligatory capital investment is an inappropriate use of debt in the capital mix. So why does it happen so much? The root cause is the unfortunate reality that clubs do a poor job of forward-looking capital planning.

A club with a comprehensive, accurate, forward-looking capital plan, backed by a capital reserve study detailing obligatory capital needs, can emulate the strong club by convincing members that as owners they should cover their fair share of depreciation in a pay-as-you-go manner. That will allow obligatory needs to be covered without resorting to debt. That one step, developing a comprehensive capital plan, would change the amount and the application of debt across the industry over time.

Applying debt for aspirational investment—growth capital—makes perfect sense. Growth capital is invested to add services and amenities that did not previously exist, which broadens the club’s appeal to prospective members. Clubs must constantly evolve to meet the ever-changing needs and tastes of the next generation of members. Upscale casual dining, resort style pools, fitness and wellness are examples of the services and amenities that have been added over the last 10 to 15 years in the industry. Debt as a tool to make those investments is a very appropriate use of debt in the capital mix. Those investments, because they broaden the appeal of the club, should yield a return on investment through higher initiation fees and/or an increase in the member count or both. The resulting increase in capital income is the return on investment.

There are certain tell-tale signs that indicate an inappropriate use of debt. As examples, debt that is continuously re-amortized but never paid down is a sign. We call that zombie debt because it never goes away. Too much debt, as has been shown with the data in this article, may be a sign. Use of debt in a reactive manner, to cover obligatory replacement, is definitely a sign. By definition, using debt for obligatory capital is reactive, rather than proactive, planning.

There are also clear indicators for appropriate use of debt. The most obvious is using debt to make aspirational investments that advance the club’s value proposition. The signal that affirms that decision is increasing initiation fees and increasing member counts which are a sure sign of successful application of debt.

A perfect example is a club that has become one of the industry’s biggest success stories over the last 10 or so years. This club has grown beyond its original location, an historic clubhouse in a major U.S. city, to encompass five additional campuses, each offering its own unique experience in the club’s trademark style. Much of that growth was funded with debt. Through the course of the club’s expansion, member counts and initiation fees have followed suit, allowing the club to pay down the debt quickly and re-leverage for additional expansion. That is a perfect example of how powerful debt can be when it is used appropriately, as a supplement to (not a substitute for) member’s equity.