Private clubs are inextricably connected to the nation’s history. From the country’s founding in which patriots exercised their freedom to associate, to today’s historic golf courses and clubs that are heralded more than a century after their construction, clubs represent a significant part of the American lifestyle.

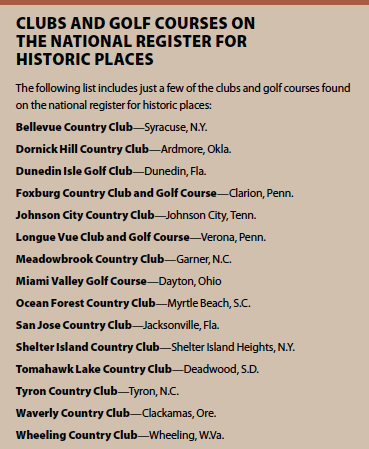

Recognizing the importance of identifying and protecting the country’s historic places, the National Park Service (NPS), a division of the U.S. Department of the Interior, created the National Register for Historic Places (NRHP). This includes the two highest historic designations, NRHP and the most prestigious, National Historic Landmarks (NHL). To learn more about the two, read the sidebar, “Levels of Designation.”

This article highlights several clubs that have earned these designations as well as the process to achieve and maintain the status.

Just a handful of clubs are considered NHLs while many more clubs are considered NRHPs, including roughly 60 golf clubs such as Augusta National Golf Club and Shinnecock Hills Golf Club. Here is a closer look at several protected clubs and the efforts they took to earn and maintain their status.

Just a handful of clubs are considered NHLs while many more clubs are considered NRHPs, including roughly 60 golf clubs such as Augusta National Golf Club and Shinnecock Hills Golf Club. Here is a closer look at several protected clubs and the efforts they took to earn and maintain their status.

BALTUSROL GOLF CLUB

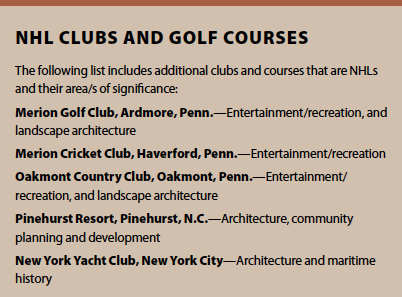

Baltusrol Golf Club in Springfield, N.J., became an NHL in the fall of 2014. Founded in 1895, Baltusrol features a pair of courses created by famed golf course architect Albert W. Tillinghast. These courses played an integral role in achieving its status as an NRHP and eventually an NHL.

At the time, Tillinghast had not yet the claim to fame that he is known for today. However, the architect took a bold approach, opting to plow through the current course to create two adjacent courses at the same time. This technique had never been tried before leading Golf Illustrated, a premier golf publication during that time, to call the endeavor the most ambitious golf course development in the country.

These “Dual Courses,” the Upper Course and Lower Course, launched Tillinghast into the upper echelon of golf course architects and, shortly after the courses opened, Golf Illustrated revered him as “The Dean of American Born Golf Course Architects.”

Becoming a Landmark

Through information provided by club historian Rick Wolffe, Baltusrol hired a consultant to facilitate the application process and joined the New Jersey Register of Historic Places in 2005. Although the guidelines for consideration to be placed on the state register are relatively consistent throughout all 50 states, Wolffe noted that New Jersey’s standards are more rigorous than others.

Upon Baltusrol’s inclusion on the New Jersey register, the application was passed on for submission for a place on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005. Because of New Jersey’s stringent rules for the state register, the move to the higher national level was relatively easy, said Wolffe.

After becoming an NRHP, the club opted to apply for NHL status. Baltusrol formed a committee compiled of Baltusrol club historians and others to help achieve the designation. However, to become an NHL, Baltusrol had to make the case for the national significance of its courses.

Significance

Many clubs have national significance. They have hosted numerous championships and legendary players; but what made Baltusrol exemplary was that the Dual Courses launched Tillinghast’s career as a golf architect. Without his ambitious endeavor at the club, Tillinghast may not have had the opportunity to create future courses that cemented his career as one of the greatest golf course architects in history.

Preservation

According to Wolffe, a key element of the process focuses on the need to maintain the property’s integrity. When Baltusrol went through the application process, an NPS official walked the course and compared it to aerial photos and noted that the course was well preserved. While the club undertook efforts to preserve the integrity of the course, some changes have been made. Wolffe noted the foresight that Tillinghast had to leave room for future designers to extend the tee boxes as golf technology improved, which Baltusrol had done.

The added protection from development was the most important benefit of NHL designation for the club. Route 78 passes just above Baltusrol, and the club expressed concerns that the government could request to build an exit ramp nearby, potentially eliminating the driving range and the first hole of the Lower Course. Landmark status helps protect the club from such an event.

THE RIDGEWOOD COUNTRY CLUB

The clubhouse, golf course and several additional buildings at The Ridgewood Country Club in Paramus, N.J., were added as NRHPs this past fall, in large part because of the work by two grandmaster architects.

History and Significance

The club in Paramus was constructed in 1929, although Ridgewood’s origins trace back to 1890. Ridgewood, like Baltusrol, started with a humble golf offering—just a two-hole course in 1890, which was lengthened to nine-holes to accommodate the game’s rise in popularity. Eventually the club featured an 18- hole course, but Ridgewood decided that this 6,000-yard course was inadequate for championships and solicited the help of now famed Tillinghast, who had built the dual Baltusrol courses a decade prior.

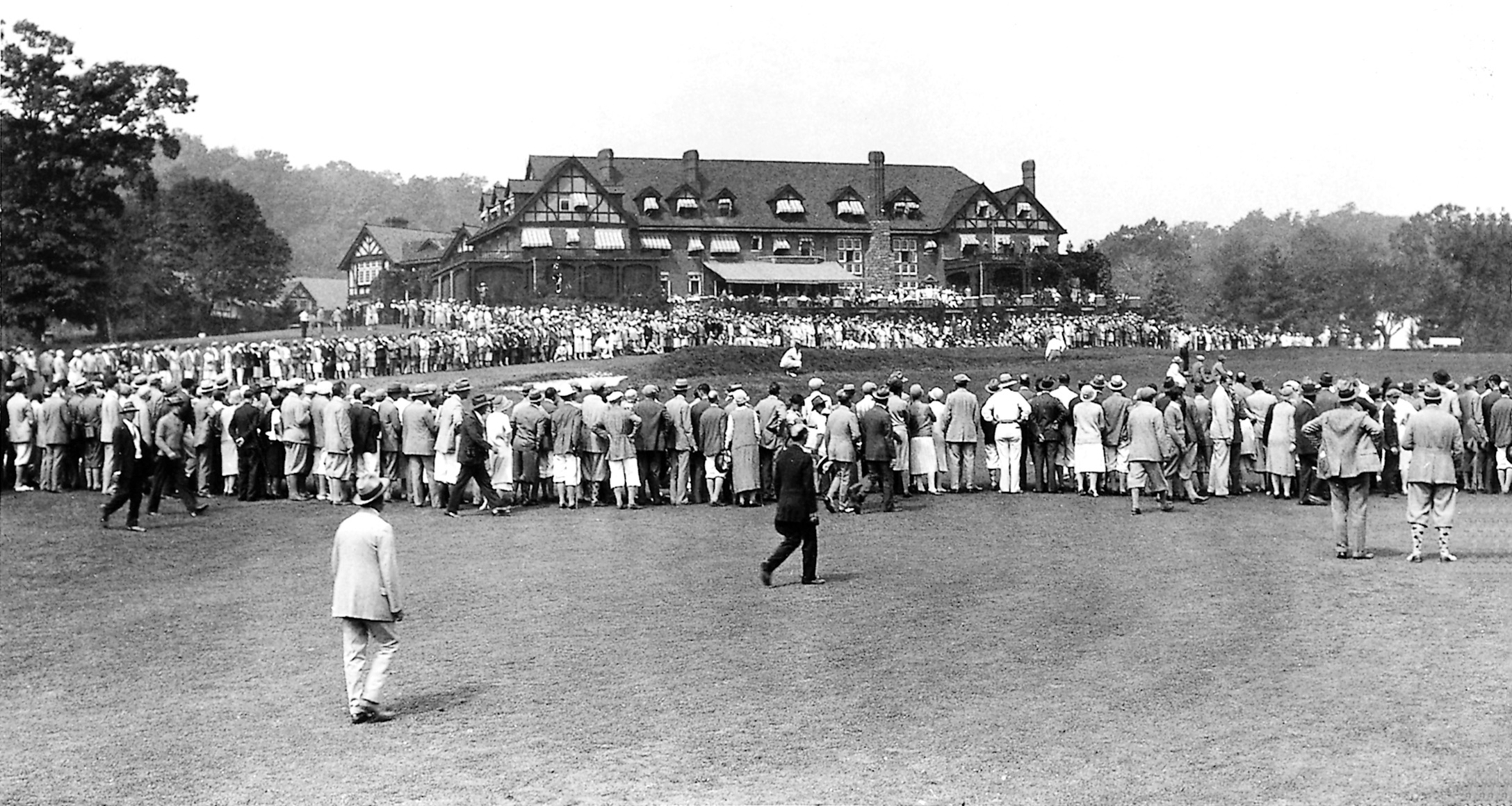

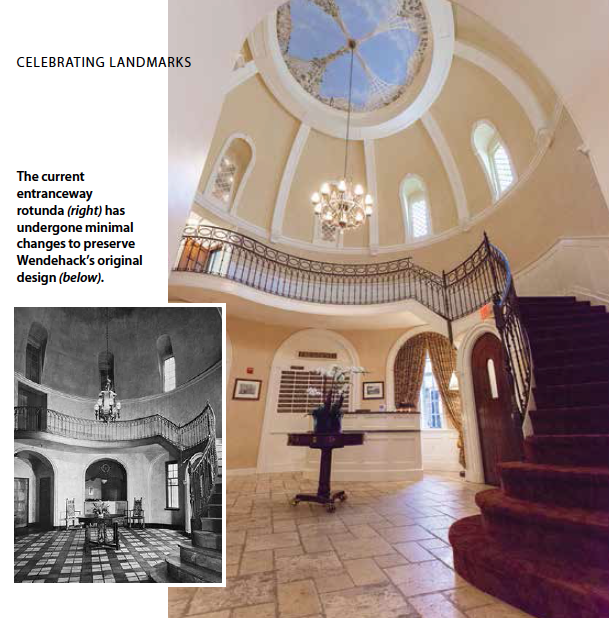

Not to be outdone, another grandmaster architect, Clifford C. Wendehack, constructed the clubhouse. Wendehack crafted the building in the “Norman” style, featuring recognizable tower and porches. The style originated in France and England nearly a millennium before, but the similar landscape of northern New Jersey and northern France inspired the architect. Both Ridgewood golf course and clubhouse opened in 1929.

Process

Process

According to David Clark, Ridgewood’s historian, Ridgewood is the only club that features a course and clubhouse built by grandmasters Tillinghast and Wendehack from scratch. The process to become an NRHP took three years, including the process of applying to be listed on the New Jersey Register of Historic Places. Like Baltusrol, Ridgewood also hired a consulting firm to facilitate the application process.

According to David Clark, Ridgewood’s historian, Ridgewood is the only club that features a course and clubhouse built by grandmasters Tillinghast and Wendehack from scratch. The process to become an NRHP took three years, including the process of applying to be listed on the New Jersey Register of Historic Places. Like Baltusrol, Ridgewood also hired a consulting firm to facilitate the application process.

Preservation

All 27 Ridgewood golf holes fall under the NRHP designation, as well as the clubhouse and several other buildings. It is important to note that its NRHP status is granted to each hole on the course, not the entire course itself. This means each of Ridgewood’s 27 holes is on the national register, and that if a hole changes too much from its original design, it may be removed from the NRHP.

Clark noted that the golf holes are remarkably unchanged from Tillinghast’s original design, but preserving the course has taken meticulous effort. In accordance to Ridgewood’s master plan, golf course architect Gil Hanse was tasked to maintain and modernize the course while remaining loyal to Tillinghast’s intent. That project and other efforts since have examined all facets of the course to ensure its integrity, and included aerial images, historic photos and even laser measurement. Hanse commented on his approach, “Ridgewood doesn’t need a golf course architect. You already have one. His name is A.W. Tillinghast. I’m going to help you find him again.”

Bunkers, greens, fairways and other parts of the course are susceptible to design changes over time. With regular maintenance this is possible. Ironically, that maintenance may be part of the reason these items change, pointed out Clark. Over time, as crews mow around these areas, they often lose their original geometric shapes.

Other changes are less deliberate and happen even more gradually. Clark mentions that trees and roughs have grown or have been cut down over time, changing the way the course is played. For example, Ridgewood has two holes where the fairways originally touched. Over time, a rough developed, separating the two fairways and the way the course was played. The master plan renovations corrected this and returned the fairways to their original form. Some additional changes also were made to the course. Like at Baltusrol, tee boxes were expanded to accommodate better equipment.

Preserving the Intent

The board plays a critical part in observing changes that could affect NRHP status, said Clark. A board that understands that courses are dynamic and thus ever-changing is critical to conducting routine checks to ensure that the course not only has its original layout, but also is still played in the same spirit as originally intended. Clark mentioned an example where apples trees were planted on one hole. This not only altered the way the hole was played but went against the style of play that Tillinghast originally intended. It forced many golfers to take pitch out shots, which the architect believed to be one of the most boring shots in the game.

The board also helped create Ridgewood’s master plan, which was critical in preserving the course and earning the club’s place on the national register. However, Clark noted that Tillinghast warned club boards that making numerous small changes over time would eventually make the course unrecognizable to its original design.

THE PLAYERS

The Players, located in the historic Gramercy district in New York City, has a rich history and earned NHL status in December 1962. In March 1966, The Players became a New York City Landmark, of which there are only 113. NCA interviewed Michael McCurdy, club treasurer, and Mary Workman, club member and president of The Players Preservation Fund, a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization dedicated to keeping the building well-preserved.

History and Significance

The Players in New York City was co-founded in 1888 by Edwin Booth, celebrated actor and brother of the notorious assassin John Wilkes Booth. The club’s purpose was to bring actors in contact with various businessmen, writers and other creative artists.

The club has been host to several notable members from American history, including Gregory Peck, Sidney Poitier, Nikola Tesla and Mark Twain (co-founder), according to the National Theatre Conference. Remarkably, Mark Twain’s poker table is still in use, said Workman. Historic production props, costumes and even the room where Booth lived from 1888 until his death in 1893 have been preserved.

Although the club’s history is rich, its relics and famous members are not the primary reason why The Players gained NHL status—the club’s exterior architecture is the main reason for the designation. Stanford White, a much-heralded architect during America’s Gilded Age, designed the club f açade. The club building was constructed in 1845 in the Gothic Revival Townhouse style. When White was contracted to remodel the façade, he incorporated the Gothic elements into the Italian Renaissance Revival Style portico.

açade. The club building was constructed in 1845 in the Gothic Revival Townhouse style. When White was contracted to remodel the façade, he incorporated the Gothic elements into the Italian Renaissance Revival Style portico.

It is important to note that only the club’s exterior is landmark and therefore does not preclude the club from revamping, renovating and making other changes to the interior.

Preservation

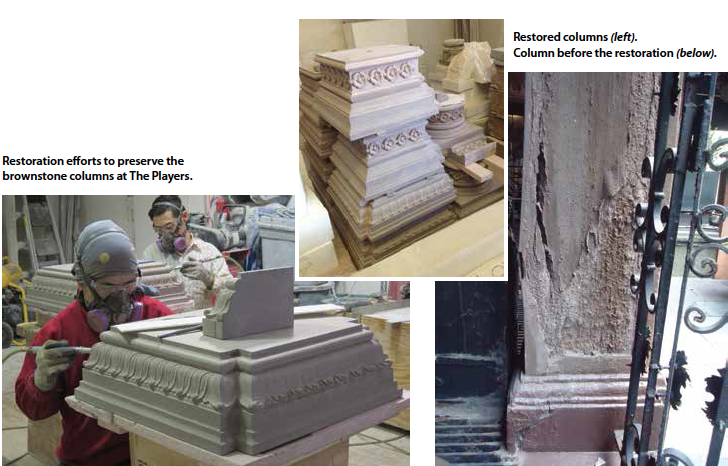

The Players Preservation Fund has been integral in keeping the club in its original form. In 2015, The Players won the 25th Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award from The New York Landmarks Conservancy. Workman pointed out that the architect went to great lengths to ensure White’s original design remained intact.

The building that eventually became the club was built 1845. The quality of that stone is still intact today, but when White was contracted in 1888 to construct the façade, the new stone was of poor quality, said Workman. Over the years, the club had made attempts to fix the stonework, but not until recently did the club take a comprehensive approach to restore the façade. Using historic photos and various techniques to identify the architecture’s true color and design, the club was able to restore the metal work, carvings, glass, iron railings and gas lamps to their original form (see photos above). The Players’ gas lamps, which are still in use, are one of the few remaining examples in the city.

Celebrating Club History

These clubs mentioned not only have a tremendous history, but are committed to preserving it for the future. They and many similar clubs have stood the test of time, and now, because of their protected statuses, can continue to stand unchanged in honor of their historic pasts, connecting today’s members with their predecessors.