This is the third and final article on member loyalty based on a research partnership between the National Club Association and researchers at Iowa State University. If you’ve read the first two articles in this series, you already know that member loyalty is arguably the most important aspect of your job. In the previous two issues of Club Director, we looked at loyalty to identify factors that perhaps have been overlooked. In the first article, we showed that reinforcing a member’s sense of ownership can lead to greater loyalty levels. We also showed that loyalty is increased when members actively think about the social benefits of their membership.

The second article examined loyalty in greater detail and showed that loyalty consisted of both what a member thinks about their club and how often they actually frequent their club. Both aspects are subject to different influences. The second article took a detailed examination of how members build attachment toward their club and how each aspect ultimately leads to loyalty. We showed that satisfaction is the primary driver of loyalty and fundamentals are most important to service.

In this article, we will discuss service quality—the primary driver of satisfaction. The topic of service quality in private clubs poses several challenges. First, how do we define what it is? Service quality is one of those concepts where everyone interprets it a little differently. Unless that challenge is addressed, we cannot measure it and hence, we have no way to mark improvements. This article describes how we developed a tool that measures service quality while incorporating these varying opinions. Second, clubs are unique not only because members’ needs are different from those of restaurant or hotel guests, clubs are unique to each other. Some clubs have golf courses, some have pools, and some have tennis courts while other clubs have none of these.

Although a measurement tool that is specific to every club would undoubtedly be most accurate, development and implementation would be impractical. Instead, we identified those service quality factors that are common to most clubs. These items were then grouped according to what aspect of service quality they target. These service quality aspects then inform your improvement decisions that are unique to your club. Finally, it is self-evident that to understand how members view service quality, their input should be sought. Unfortunately, current service quality research largely excludes member input because many clubs are hesitant to allow data collection. Surveying members is often seen as an intrusion. If this research partnership has one strength, it is that the data was sourced from members themselves and is therefore more accurate.

Overview: Service Quality

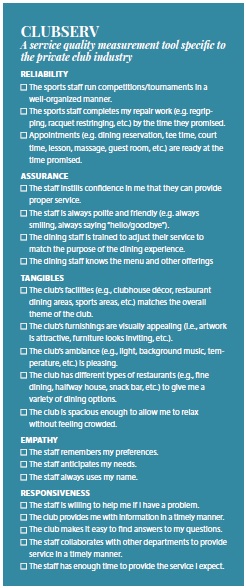

In the late 1980s, three researchers set out to discover the most basic aspects of service quality regardless of what type of industry was in question. They studied banking, automobile repair, phone companies, credit card providers, and several other industries. In general, they found that service quality involved five different aspects: reliability, assurance, tangibles, empathy, and responsiveness. They called their model SERVQUAL. Over the next 40 years, researchers have refined the SERVQUAL model to better fit individual service industries. Models have been developed for restaurants, theme parks, hospitals, websites, and many others but until now, a model specific to the private club industry has never been developed. We named our model “CLUBSERV.”

Reliability: Regardless of industry, customers consistently list reliability at or near the top in terms of importance. Customers want to know that the service they’ll receive this time is just as good or better than the service they received last time. The reason is a simple math equation. Satisfaction is essentially the difference between expectation and experience. When the service received is superior to what was expected, the customer is satisfied. The converse is also true. A customer’s expectation is derived from their previous service encounters. Thus, if a customer received good service last time, they will expect it this time. When that expectation is not met, poor satisfaction is the result. However, if they received poor service last time, their current expectation is also lower and the difference results in higher satisfaction.

Assurance: Assurance pertains to the confidence that the service quality will be high. Research has shown that when customers are not confident that they will receive good service, they report lower levels of satisfaction regardless of the actual level provided. When a customer is apprehensive, they cannot enjoy the service even if it is otherwise flawless. It is important that the customer feel at ease for good service to be recognized. Customers can be reassured by something as simple as a smile; a smile conveys friendliness and says to the customer, “nothing is wrong, I have everything under control.” Assurance also encompasses staff knowledge and training. For example, when the dining room server is well trained on the menu, the guest will trust that the meal will go smoothly and will then focus on enjoying the experience.

Tangibles: This describes the aspects of service that can be seen or touched. For example, when a member walks through their club they can enjoy the art on the walls or feel the comfortable furniture when they sit down. Tangible items are important for two reasons. First, certain tangible factors contribute to overall service quality. For example, an employee uniform that is unkempt detracts from the overall experience. Second, the other aspects of service are intangible which makes potential members risk-averse to joining. A potential member cannot “test drive” assurance, reliability, and so forth so they will look to the tangible aspects as predictors of potential service quality. Have you ever driven into a club that had weeds in the landscape or cobwebs in the porte cochere? Do you instantly make some sort of inference about the service quality you’re about to receive? Potential members do the same thing.

Empathy: This has been described as the caring and individualized attention that is paid to a customer. For example, is the server friendly? Is the club open when you need it to be? Does the staff remember your name and your preferences? Do they make you feel important? In industries characterized by a high level of personal interaction (e.g., healthcare, hospitality, education, etc.), empathy is extremely important. Not only does empathy involve the niceties of polite society (warmth, smile, eye contact), it also includes the degree to which the customer’s needs are considered. The classic example is banks. Once upon a time, banks closed before most people could visit. Once they realized that longer hours provided better service, banks began closing later and opening on the weekends.

Responsiveness: In short, responsiveness means “lack of hassle.” Great service should not be a bother for the customer. Phone trees, employees who cite “policy,” and being put on hold, are things that are extremely frustrating to customers. In the same way that service that lacks empathy makes the members feel unimportant, a club that is unresponsive makes them feel like they do not matter as well. Members want to feel valued. Your members are spending a tremendous amount of money at the club. Furthermore, the longer a member has to wait to spend money at the club, the more chances they have to spend that money elsewhere. Make it as easy as possible for members to use the club.

CLUBSERV Development

We began by compiling an exhaustive list of every item that described service quality in private clubs. We consulted industry trade journals, academic literature, and informal discussions with club members and professionals. We then categorized these potential items by club area. We included items on dining, landscape, golf (including pro shop, course and tournament management), aquatics, and so forth. Our preliminary list was nearly 200 items long. Obviously this was too many to be useful, but it gave us a starting point and allowed us to fine tune and clarify the list.

We then consulted a panel of club experts of various types. We had club board and committee members, rank & file members, club consultants, senior club managers and middle managers from several venerable clubs. We asked them to assess each item as to how well it described service quality. We also asked them to identify any items that were unclear and to suggest wording improvements and/or new items that they felt were needed. We repeated this process several times until there was a general consensus as to what items were most important. Then the items were classified into the five SERVQUAL dimensions discussed above. To simplify the list without severely limiting their accuracy, items which were similar across several departments were combined. For example, the items “the golf staff run tournaments . . . ” and “the tennis staff run tournaments . . . ” was combined to “the sports staff run tournaments . . . ”. We ended with nearly 70 items that our panel agreed did a good job of describing service quality.

Again, a list of 70 items was too long to be useful in practice. Furthermore, while we were confident in the list’s accuracy, it was still only the opinion of a relatively small group of experts. Next, we asked a large group of actual club members to rate our list of 70 items. Based on their answers and some statistical analysis, we removed items that had too much disagreement among the members. We were left with 27 items which had widespread agreement. That list was given to a new group of members to confirm its accuracy. The confirmation revealed 20 items that accurately described service quality within private clubs (see sidebar). This was our final measurement tool—CLUBSERV.

You may be looking at the CLUBSERV list and thinking to yourself, “What about ___, isn’t that important?” Indeed, there are many aspects of service quality and a list of 20 items is far from exhaustive. Remember, we began the process with a list of nearly 200 items which was quite literally, everything we could think of. However, the purpose of CLUBSERV is to define as closely as possible what service quality means and to do so as efficiently as possible. CLUBSERV captures 87.8% of what our sample group collectively defined as service quality—and with only 20 items. In other words, another item may measure a distinct aspect of service quality more closely but there would be measurement gaps elsewhere. Adding more items would capture more of what service quality means but the survey would be longer and only marginally more accurate. These 20 items provide the most parsimonious measurement tool currently available.

How to Use the Findings

So, what does this mean? First, you now have a simple tool to measure service quality at your club. Your members can complete a 20-item survey in less than five minutes. This is far less intrusive than bombarding your members with a long survey that frankly may not be as accurate. The entire process of developing CLUBSERV was focused on being able to quickly and accurately measure a concept that defies measurement. We consulted industry experts to guide us but ultimately, our results are the aggregate definitions of hundreds of club members themselves. With the few items listed here, you can easily measure service quality and be confident that you’re actually measuring what you think you are. That is, what does a member consider service quality.

Second, CLUBSERV is a consistent measurement tool meaning the accuracy of your results will not vary a great deal from one survey to the next. This allows you to create benchmarks and track improvements over time. It is important to examine trends over time rather than individual movements. Average scores can vary slightly from one month to the next due to simple randomness but over time these minor variations will even out, and you can assess how member opinions are changing.

Third, this tool allows you to identify which aspects of service quality are strongest and weakest in your club. Rather than looking at each item itself, concentrate on the average scores of each dimension (reliability, assurance, tangibles, empathy, and responsiveness). This will indicate where you should concentrate your attention. For example, if the three reliability items show consistently high scores you can be confident that your members believe the club is providing reliable service in general. On the other hand, if the four assurance items average lower than desired it would suggest a potential weakness. You would then want to focus on improving member confidence. Perhaps improving training programs is needed or maybe it is something as simple as reminding your staff to smile more. By maximizing your strengths and improving your weaknesses, ultimately your service quality reports will improve.

There was one final point that most experts and members seemed to agree upon: the importance of getting the fundamentals right. This was made abundantly clear. Throughout the process participants consistently rated items related to service fundamentals as highly important to service quality. Items which might be considered “nice to have” scored much lower in importance and there was a much greater disagreement among participants. We were forced to remove these items because they did not get to the heart of service quality. Certainly, these unexpected touches are important when differentiating between great service and that which is truly superlative, but they are unimportant if the basics are not met. Getting mints with the check at the end of dinner may be a nice idea that a member might not expect. It might even improve their rating from highly satisfied up into the truly delighted range. But if the server was impolite taking the order, the best mints in the world will do nothing to make that member more satisfied.

This brings us to the third and final paper to come from this study. We wish to acknowledge the National Club Association for their generous support with data collection without which this study would not have been possible. We look forward to future partnerships as well. We would also like to thank the anonymous clubs and their members for their time in completing the surveys.

Dr. Fredrick “Chuck” Meitner is an Assistant Professor in the Hospitality, Recreation, and Tourism Management Department at East Stroudsburg University and recently received his PhD in hospitality from Iowa State University. He conducts research on private club member behavior, service and operations management and mental health among hospitality workers. He is also an aspiring sommelier. Chuck has 20 years’ experience in private clubs, both in the kitchen and the dining room. He can be reached at [email protected].

Dr. SoJung Lee is an Associate Professor in the Apparel, Events, and Hospitality Management Department at Iowa State University. Her research focuses on consumer behaviors in pop-culture tourism, club industry, rural tourism, and sustainable tourism from psychological perspectives. Her current research projects include clubs’ environmental sustainability and members’ psychological and sociological behaviors. She can be reached at [email protected].