Natural disasters can wreak havoc anytime and anywhere. Clubs are particularly vulnerable to these disasters, which cause tremendous damage to the club campus and its facilities, club members’ homes and the homes of staff. The National Club Association surveyed clubs across the country that have experienced recent natural disasters to learn more about their recovery efforts to provide valuable lessons and best practices in this area.

Natural disasters can wreak havoc anytime and anywhere. Clubs are particularly vulnerable to these disasters, which cause tremendous damage to the club campus and its facilities, club members’ homes and the homes of staff. The National Club Association surveyed clubs across the country that have experienced recent natural disasters to learn more about their recovery efforts to provide valuable lessons and best practices in this area.

The Plan vs. Reality

Most of the clubs felt prepared or fully prepared for the oncoming disaster. River Oaks Country Club in Houston felt most prepared, but even with proper planning and preparation, could not avoid the unexpected and costly consequences of Hurricane Harvey in September 2017. Among some of its preparations in its 60-page planning document were grounds preparation and emergency communication plans for membership and staff. Despite the club’s preparedness, roads to the club were impassible, complicating the response and recovery as staff and crews could not access the campus until it was safe. Repairs, primarily for the golf course, totaled $15–20 million.

Similarly, Houston Racquet Club aimed to protect itself from water damage, using sandbags and storing electronics on higher ground or away from flood-risk areas. The club gauged the number of sandbags necessary using 2001’s Tropical Storm Allison as a reference—at the time, it caused the Houston area’s worst flooding in history.

Palmira Golf Club in Bonita Springs, Fla., initiated standard emergency procedures for Hurricane Irma, also in September 2017. For example, the club removed objects that could become projectiles and moved equipment to higher ground to prevent flood damage. The club also worked with its local emergency response teams and insurance carriers in the lead up to the storm and crafted a communications plan to club employees and members.

Bald Peak Colony Club in Melvin Village, N.H., had emergency plans but no formal disaster plan when a severe windstorm struck. Unfortunately, due to the unexpected severity of the storm, the club had little opportunity to prepare for a weather event of this magnitude—what was forecasted to be a normal New Hampshire snowstorm turned into a windstorm with gusts of more than 100 miles per hour that toppled roughly 10,000 trees on its campus.

The Tubbs Fire in October 2017 was California’s most destructive wildfire on record, destroying 360,810 acres and 5,643 structures, incurring $1.2 billion in damages. The Fountaingrove Club removed tall trees near the clubhouse, installed efficient sprinkler systems, trained staff in fire protocol and safety, and even hired sheep to eat tall, dry grass and underbrush near structures. While Fountaingrove made preparations to protect itself, the historic fire still overwhelmed the club. Damages and Downtime The damage caused by each disaster was significant for all surveyed clubs, requiring them to close down facilities for at least a week, and in the case of Fountaingrove, for months. Palmira’s clubhouse was closed for more than two weeks due to water and mold damage in addition to being without power for an extended period of time. Its three 9-hole courses were closed from three to six weeks. Fortunately, most members were in the North when the disaster struck, allowing the club staff to focus on getting the club back up and running. Houston Racquet Club’s damages were widespread. Its fitness center was without showers or restrooms for a week while its clubhouse was down for three weeks. The club’s lap pool was nonoperational for a month and its resort pool remained closed for two months after the disaster. Bald Peak was already closed for the season, so members were away from the club, easing recovery efforts. The club also asked members to stay away from the campus fora few weeks following the storm. As a result of the disaster, the golf course opened two weeks later than normal. Because of the 10,000 trees that were lost, a few holes now play differently and the one- mile front entrance to the club has been altered.

River Oaks’ golf course was down for more than a week before golfers returned. The club also shortened its course for several months while it repaired its holes. The ability to play all 18 holes on the course required more than six months of effort.

Fountaingrove suffered extreme damage (see “Rebuilding from the Ashes,” Club Director, summer 2018). Six structures burned including the clubhouse, fitness center and maintenance buildings, totaling 40,000 square feet of space, and more than 1,000 trees were lost. Damages are expected to cost more than $50 million. The clubhouse, fitness center and golf course maintenance buildings are still being designed and permitted a year-and-a-half after the fire. Fortunately, the athletic center, pool and activities center were spared. The athletic center is currently the hub of the club. To get members back on campus, the club installed high quality, temporary facilities which the members have enjoyed.

Recovery Efforts

Club staff was critical in each club’s immediate recovery efforts. In some cases, advance preparation helped. Before Hurricane Irma hit, Palmira ordered food, water and ice. Once the storm hit, the club fed staff that were able to return to work using gas stoves and portable generators. The club began its remediation and restoration on the clubhouse first, then worked outwardly from there. Palmira also relied on nearby clubs to coordinate recovery efforts and to help access vendors such as tree removal specialists. The clubs developed a system to share the vendors in which a vendor would work at one club in the morning and a different club in the afternoon.

After ensuring all workers were safe, the Houston Racquet Club met with available staff and worked to get tennis courts back in operation first. The club prioritized the tennis courts because cleanup was a simpler task. COO Thomas Preuml said the club focused its recovery efforts so members could get back to the club. Once the clubhouse’s newly renovated dining areas were back up and running, F&B operations reopened even while other repairs were ongoing. This helped to communicate to members the storm’s impact and the progress the club was making. For instance, temporary restrooms had to be brought in due to waste- water lift stations being destroyed during the flood; however, members were dealing with similar situations at their homes, so they were very understanding.

Coincidentally, the club was undergoing a renovation when the hurricane hit. The contractor was still onsite at the club and generously gave attention to Houston Racquet Club. Preuml noted how difficult it would have been to access a contractor otherwise. Additionally, employees, regardless of department, were offered the opportunity to help with the cleanup for extra pay. Bald Peak enlisted all available crews to immediately start working to get the club running again. Because Bald Peak and Palmira were in their off-season, the clubs were not fully staffed, it made the recovery that much more challenging.

In addition to helping staff get back on their feet so they could return to work again, a challenge for River Oaks was providing safe access to the club. As all the roads to the club were impassable, it made it more difficult for the club to get “all hands on deck” to begin recovery operations. In preparation for a future disaster, the club intends to have more staff on hand to help get the club operational more quickly.

Fountaingrove’s clean-up process began quickly. Generators were installed after the fire to operate wells to water the golf course, and an offsite commissary kitchen was hired to feed members and staff. The club also partnered with the city of Santa Rosa and the Salvation Army as an official “comfort station” for the Fountaingrove community. Other organizations like Google and FEMA also contributed with crisis counselors and food trucks. Daily conference calls were held immediately following the fire with membership and staff.

The club also needed to set up temporary facilities to keep the club operational. However, the city was very difficult to work with on these structures. Since they were needed for more than 12 months, the city considered them permanent facilities and required extensive planning, zoning, fire code and permitting requirements. Members were very understanding of situation, and the experience brought them together as a community.

Improving the Plan

Each club plans to add new procedures to prepare for future dis- asters. Improving communication was a theme for several clubs. At Palmira, the club is developing a better communication system with staff and the board, whether through different cell phone carriers or SAT phones. One recommendation the club is considering is whether to have cell phones from multiple carriers in the hope to have service even if one carrier’s system is down. The club would also reach out to recovery vendors prior to another storm to ensure the club had access to generators for electrical power.

Each club plans to add new procedures to prepare for future dis- asters. Improving communication was a theme for several clubs. At Palmira, the club is developing a better communication system with staff and the board, whether through different cell phone carriers or SAT phones. One recommendation the club is considering is whether to have cell phones from multiple carriers in the hope to have service even if one carrier’s system is down. The club would also reach out to recovery vendors prior to another storm to ensure the club had access to generators for electrical power.

Houston Racquet Club has made changes to its communications system by installing a new critical communications plat- form from Rave Mobile Safety, also utilized by the Department of Homeland Security. The emergency system can send texts, emails and phone calls to specific audiences with varying levels of urgency within moments. For its efforts, the Houston Racquet Club won first place at CMAA’s Ideas Fair in the Safety Programs and Risk Management category.

Bald Peak pointed out that a communication strategy was key to handling multiple media requests. Club leadership felt that media communications were handled well. This process reiterated to the club the importance of having a formal media response plan. The club is also developing a formal disaster plan.

River Oaks will test its annually updated plan by brainstorming how to respond to unexpected scenarios caused by disasters. Roads providing access to the club were impassable due to flood waters for four days, a scenario which was not anticipated prior to Hurricane Harvey.

Fountaingrove learned that in a fire of this scale, government resources were strained and could not provide adequate protection. Firefighters were tasked to save lives, not structures, magnifying the damage done to the club. To improve its disaster plan, Fountain- grove plans to add new equipment such as firefighting tools to stop or mitigate damage if conditions are safe to use them. The club will also enhance its communications resources to keep in contact with staff and members after experiencing difficulties in keeping in touch with staff who were evacuated for several weeks.

Communication is Key

With each club sustaining significant damage—including primary club facilities and member homes—it was critical that the clubs maintained strong communications with members and staff. However, with most clubs without power, clubs had to create new systems of communication. Most Palmira members (about 70%) were not in the area when the storm arrived. While fortunate for member safety, this meant that members needed immediate updates on the conditions of their homes and the club. In all, close to 50 homes had fallen trees and 400 of the 821 homes required new roofs. Palmira sent members a video of the community and explanation of damages sustained to the club and surrounding properties. The club developed a plan to update members twice a week to keep them informed of the recovery process.

Palmira was without power post-storm for a week. The club relied on staff cell phones and laptops—and staff with power in their homes—to send member communications. One department manager (with electricity) acted as the club’s point of contact with vendors and insurance companies. General Manager/COO Mark Neneman sent the manager member communications that were then forwarded to a communications employee who spends summers in Connecticut to distribute to members.

Communicating with members and staff was one of Houston Racquet Club’s biggest challenges from Hurricane Harvey. The club’s communication’s systems were down for several weeks post-disaster. The club’s IT manager worked to ensure the club was online as soon as possible, though at a slower speed because high-speed fiber lines were nonoperational. During that time, the club used cell phones to reach members and staff and manually inputted point of sales data. After sending an initial summary of damages via email, the club sent members weekly updates on the recovery progress.

According to Wyles, the club can never communicate too much during a disaster. Like Palmira, Bald Peak was struck when the club was not in operation. The New Hampshire club also resorted to an improvised communications system, relying on available means of communications (email, text, phone calls, website) to reach members. Wyles used his cell phone’s hot spot to connect to the internet.

Many members who were out of town when the storm hit called for updates and to check on the status of their on-campus homes. The club sent photos and drone footage—and, in cases where members suffered more significant damage, Wyles called members directly to discuss the situation.

Fountaingrove also relied on phone calls, text messages, email and even Facebook to reach members and the community. The club communicated to members and staff that despite the club being heavily damaged, Fountaingrove would survive the dis- aster and staff were reassured that their jobs would remain. River Oaks maintained power during Hurricane Harvey.

Post-disaster, the club sent emails daily, then weekly up until the club was fully operational to keep members and staff informed. The club focused on providing effective updates that were timely, useful and accurate.

Taking Care of “Family First”

Taking Care of “Family First”

In all the recovery efforts, staff was critical to get the club operating as quickly as possible. However, as the club is affected, so are staff. Every club reported having staff out post-disaster, ranging from a few days to nearly a month. At all clubs, staff were also compensated during their time away from the club.

In all the recovery efforts, staff was critical to get the club operating as quickly as possible. However, as the club is affected, so are staff. Every club reported having staff out post-disaster, ranging from a few days to nearly a month. At all clubs, staff were also compensated during their time away from the club.

Bald Peak had a “family first” mentality when engaging staff and vendors who helped the club recover. Because the club was in its off-season, Bald Peak had a fraction of its employees on hand to help with the recovery process and heavily relied on outside vendors.

Most staff were able to work immediately following the windstorm, with some snowshoeing to the club, said Wyles. He noted the importance of treating each person who helped well, giving them the attention, care and instruction they need.

Palmira raised money to help affected staff. The “Palmira Strong Program” was instituted to raise money to help employees get back on their feet. Members collected funds for staff that lost homes or suffered damages from the storm. The club also housed 15 staff during the storm to provide a safe place for employees as well as to have workers available to help with the recovery.

River Oaks held a drive as well to collect and distribute clothing, food, cleaning supplies and other items staff and members would need. The club already had an emergency employee assistance fund, funded by employees to help each other in times of crisis. Members also donated to help staff impacted by Hurricane Harvey.

Employees of other local clubs were also severely impacted by the flood waters, so the donation/assistance center River Oaks had established was made available to affected employees of area clubs and restaurants. Donations came from members, staff and even clubs in Arizona including Desert Mountain Club and Desert Highlands Golf Club, among others.

Financing the Recovery

With expansive grounds and numerous facilities, clubs are particularly vulnerable to widespread damages resulting in significant costs. From property and casualty coverage to flood insurance and “tee to green” and wind policies, clubs need a strong understanding of what insurance companies and brokers will cover and the types of comprehensive coverage needed to protect club assets. One club elected not to participate in the survey due to a pending dispute with its insurance provider.

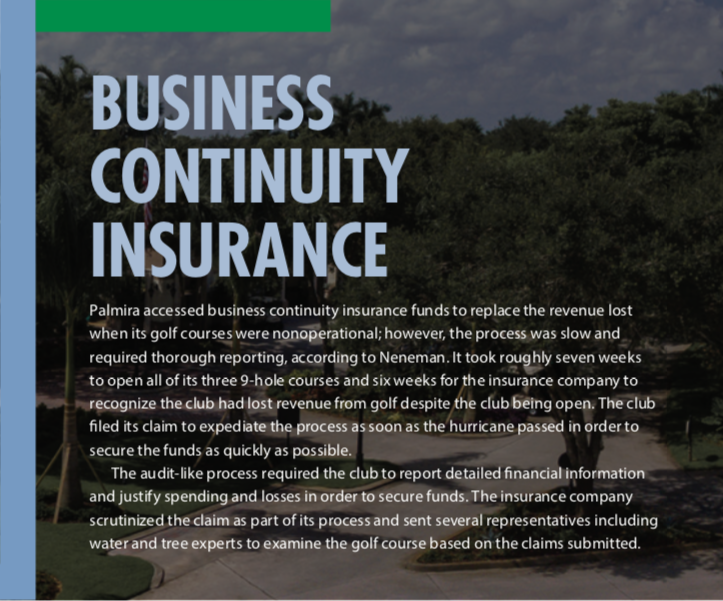

For each club, insurance covered a different percentage of dam- ages. Palmira experienced $625,000 in damages and lost revenue, which insurance covered at 76–100 percent. Prior to the Hurricane Irma, the club documented its grounds and facilities in order to indicate damages done by the storm. Palmira used a drone, photos, video and mapping to accurately record the club’s condition both before and after Irma. After the storm passed, insurance systems were strained due to numerous claims throughout Florida as well as from claims from Hurricane Harvey that struck just a few weeks prior. This slowed the entire recovery process as the club had to wait for appraisers to review damage.

Neneman noted the many nuances of the insurance system. In certain coverages, how much coverage an insurance provider offers can be related to how far the club is from the eye wall and category level of the storm, making it critical for clubs to under- stand the extent of their coverage.

Fewer insurance carriers are providing tee to green or wind coverage as well, he added, and when they do, it is very con- trolled. Palmira included specific riders to its policy to help with the diminished coverage.

Insurance covered roughly 51–75 percent of its $1.8 million in damages to the Houston Racquet Club. Their flood policy was at the maximum for property and contents for what was available for a business located in a flood zone. Damages exceeded coverage.

At Bald Peak, insurance covered between 26 and 50 percent of its $350,000 damages. Wyles commented that the insurance process was slow as well. The insurance company hired a third- party underwriter, which required additional oversite from Wyles in order to ensure the desired outcome. The club also has a PGA endorsement on their policy which added funds for tree cleanup and removal. The club’s Insurance Committee was apprised, involved and helpful during the process, said Wyles.

Bald Peak had a clear, defined timber harvest program which in part consists of salvaging timber that is designated to be cut. With thousands of trees suddenly downed, revenue from this source came to fruition much earlier than anticipated, which was able to help pay for uncovered damages.

Insurance covered less than 25 percent of River Oaks’ $15–20 million in estimated repair costs. Much of the damage was to the golf course, complicating the insurance process. One of the club’s challenges was finding the appropriate costs for the repairs and determining what was covered by insurance.

Fountaingrove’s insurance claim was the largest its carrier ever had. Matching the experience of other surveyed clubs, the claims process was slow. However, more than half of the club’s damage was covered.

All responding clubs except Fountaingrove had disaster reserves on hand. However, Fountaingrove had a policy that helped with recovery costs for lost dues and usage revenue. The two Houston clubs leaned on members to help cover costs for damages and repairs. Houston Racquet implemented a temporary dues adjustment for six months to maintain its cash balance and River Oaks initiated a member assessment. Other Considerations

Neneman made sure to keep the board informed of the recovery process, especially related to club finances. The board president, treasurer and executive committee were very involved because the club was spending money outside of the norm. Palmira’s board president served as the main point of contact and approved spending as needed to restore the club.

River Oaks General Manager/COO Joe Bendy pointed out that the club had experienced “post-storm guilt” from Hurricane Harvey. While the club campus experienced heavy damage, many residents and businesses in the area were more seriously impacted by the storm, creating headlines nationwide. Many fundraisers on the club’s schedule were either cancelled or had lower than expected attendance and giving because, as Bendy put it, “who wants to go to a party when so many fellow citizens are suffering?”

Impact Today

More than a year later, the clubs are still recovering in some form. At Palmira, roofs are still being replaced. River Oaks’ just began repairs on the damage along the Buffalo Bayou River, and its golf course is still under repair and should be fully recovered by year’s end. Bald Peak’s entrance will never look the same, and Fountain- grove is still in the depths of its recovery.

Despite the hardships, each club noted that the recovery effort brought members, staff and communities together through their shared disaster experience.